We live in times, which Arendt would call “darkening times for democracy”. Lene Auestad, leader of the “Psychoanalysis and Politics” movement reads Arendt’s concept as a description of “moments in history, when public speech fails to illuminate”, and I would add, even more, it fails to enlight.

For me, these are times, in which inexusable events happen; events, thinking for which gets “stuck” due to deficiency of modes and modalities of the mind: disgraces, such as the “Ivantcheva and Petrova” case (mayors of Mladost municiplaity in Sofia who were framed because of their work against construction works and are now facing severe charges and are imprisoned under inumane conditions); the case of the arrested two investigative journalists while photographing the burning of documents surrounding the #GPGate affair in Bulgaria; the Bulgarian Constitutional Court voting the term “gender” unconstitutional on the background of severe and pervasive violence against women and children; the expressed outrageous attitudes of politicians towards protesting mothers of disabled children; systematically creating conditions for the burn out of care providers to an extent that new-borns are being severely beaten by midwives, women in labour being murdered by means of springing upon their belly, toddlers are harassed and beaten by their governesses in the kindergarten; and many more disturbing precedents from the recent reality in Bulgaria.

One should not miss out from this list ongoing evacuations, in the sense of evacuating toxic and even radioactive psychic material, via projections into those who are different, like the scapegoating of Roma, for example – such phenomena have not gone, but have been expanded by other phenomena with the same function, say the projections into refugees and people seeking international protection.

In Europe, as well as in the so called democratic world more widely, very similar things happen, especially with the rise of the far- right on the everyday and on the official pollitical and societal levels.

I talk with young, bright people and I follow the moods on social media. Such phenomena, as the listed above, evoke in us bolackages of thought and a specific stuckness, which necessitates a new modality of our professionalism – as psychologists, or as whatever we call our work with the individual and the collective psyche, a modus which I call “the nausea as a modus of thinking” (following Sartre and his concept in the novel of the same title).

“The nausea” is different from “disgust” and “recoil” since it does not result in “vomiting” in the public space, nor does it cause withdrawal from the issues at hand.

Of course, the nausea, can also produce nothing and this is also a good outcome – as Adorno says about the only possible reaction to one of the most disgusting events in human history, the only possible response to events like the Holocaust, is silence. And that poetry is no longer possible after faschism, as a historical fact about the capacity of humanity to unchain the human condition.

The nausea is a modus of thinking, which is beyond knowing, and which is a comprehension beyong knowing – a knowing that one is beyond knowing, as well as a comprehension of that, which is beyond knowing. This is a modus of thinking, which becomes meaningful only by accessing what Levinas, for example, calls the “infinity” at the next layer beyond the collective unconscious.

The difficulties in accessing that, which is beyond knowing is also one of the reasons for the decline of psychoanalityc practice nowadays – the classical face-to-face psychoanalysis requires sustained work year after year in order to develop this type of sensibility in both the analyst and the analysand. Moreover, it requires even longer to distil meaning and to applying it in our everyday being.

The nausea is a modus of thinking about the pervert and the disgusting in the individual, the social and the political life. It has meaningmaking properties only in a group context and via artistic devices, i.e. the psychologists and other practitioners who seek to work at this levels of the disgusting, the dregs of the public sphere, which is also the most needed at the present moment work, need a spesific equipment as well as a collaboration with professionals from other fields specialising in knowing, not only those from the scientific sphere and from the professional community.

One way to resist the nausea is by accessing deeper layers of the unconscious in a group, or what Gordon Lawrence called “the matrix” – a womb created by the minds of those who participate in real or in imagined ways in a group or a community, a womb in which, as Bion said, the thoughts are in a search for their thinker and are born by the storm of minds. The work with free associations, transferance and counter-transferance, though, is not sufficient when we work in the “mud”, the most challenging social fields, whic Trist calls the “problematique” or just “messes”. Trafficking of human beings is one such field, in which the most perverted associations of violence, sex and money are inter-twisted and in which we face the greatest difficulties to make sense.

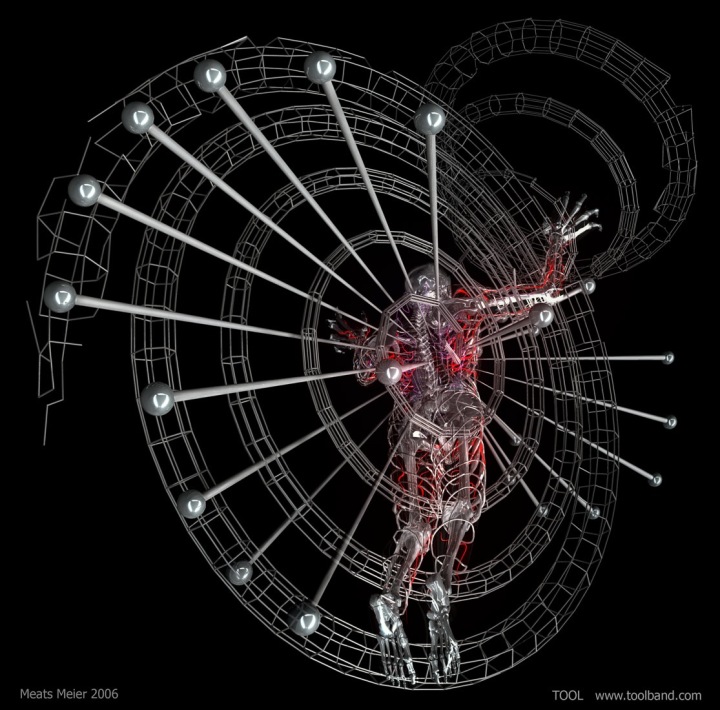

The art is isolated as a form of entertainment, as one of the “battery-charging” compartments in our difficult everyday life, together with intimacy, love, activism, which are all no longer a part of our lives but isolated spaces for retreat. The art, however, is a very serious and effective tool to access unconscious, repressed, emergent and so on material, and because of these qualities, it is a tool, which makes accessible, conceptualisable and therefore thinkable this material in the individual, social and the political space by facilitating the containment of anxieties, the management of vulnerability and the working through of traumas, so that one can be-in-the-world and can be also capable of action, even in the shape of being-in-another-way as a form of protest and resistance.

It is important to work with artists and artistic techniques, especially with music since music has universal properties and language that can produce associations in a variety of contexts and resonates with a number of people woth different attunements. The music is a peculiar type of a mediator, a research and psychoanlytic tool from a meta-analytical, second-order level of hyper-analysis.

I work a lot with visuality (with drawings, photos, video material and dreams) and I am deeply grateful to all the authors who have worked with me in my attempts to conceptualise darkening times for democracy and how they reveal themselves at the present moment – all works with modalities of the mind which allow the nausea to operate in a meaningful way and allow the psychologist, or whatever he or she calls themselves, to formulate mutative interpretations. Music and poetry particularly make a point when encountering the meaningless and that which kills meaning. Also improtant is to work with the underdog artists since they have access to the depository of the oppressed, which – as Benjamin says – is the depository of the historical knowledge.

In the scientific field, we live in times of disllved and re-drawn boundaries between disciplines. It is, I believe, the end of the roles of the psychologist and psychoanlyst as such, and their re-birth as trans-disciplinary experts, as leaders of dissent, as enlighteners/activists and as whistleblowers. Crucial in these effort is to work at the deepest levels and to provide collective interpretations and conceptual frameworks that facilitate meaning-making.

My thanks go to Plamen Dimitrov (Bulgarian Society of Psychologists) and Prolet Velkova (Darik Radio) for hosting a conversation on this, to the independent artists Stoyan Stefanov, Mitko Lambov, Bewar Mossa, Sultana Habib, Sam Nightingeil and Juliet Scott (the Tavistock Institute) for working, thinking and feeling with me (and instead of me) and to Mum for saying that all this makes sense to her.